Properties of message executions on ICP

Asynchronous messaging model

ICP relies on an asynchronous messaging model. Compared to synchronous messaging like on Ethereum, this provides performance advantages because individual messages can be executed in parallel. However, asynchrounous message execution can also lead to sometimes unexpected or unintuitive behavior. Therefore, it is important to understand the properties of message execution. Potential security issues that arise in this model, such as reentrancy bugs, are discussed in the security best practices on inter-canister calls.

The community conversation on security best practices also discusses the messaging properties.

Message execution properties

To interact with a canister's methods, there are two primary types of calls that can be used: update calls and query calls.

If the Rust CDK is used, these are usually annotated with #[update] or #[query], respectively. In Motoko, updates are declared as public func, and queries us the dedicated keyword: public query func. ICP also supports additional entry points such as heartbeats, timers, initialization or upgrade hooks.

A message is a set of consecutive instructions that a subnet executes for a canister. The code execution for any such entry point can be split into several messages if inter-canister calls are made. The following properties are essential:

Property 1: Only a single message is processed at a time per canister. Message execution is atomic and sequential, and never parallel.

Property 2: Each call, query or update, triggers a message. When using

awaiton the response from an inter-canister call, the code after theawait(the callback, highlighted in blue) is executed as a separate message.

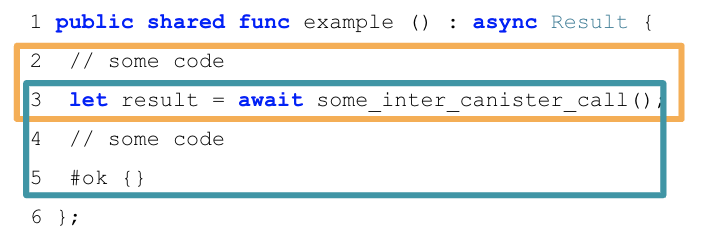

For example, consider the following Motoko code:

The first message that is executed here are lines 2-3, until the inter-canister call is made using the await syntax (orange box). The second message executes lines 3-5: when the inter-canister call returns (blue box). This part is called the callback of the inter-canister call. The two messages involved in this example will always be scheduled sequentially.

Note that an await in the code does not necessarily mean that an inter-canister call is made and thus a message execution ends and the code after the await is executed as a separate message (callback). Async code with the await syntax (e.g. in Rust or Motoko) can also be used "internally" in the canister, without issuing an inter-canister call. In that case, the code part including the await will be processed within a single message. For Rust, both cases are possible if await is used. An inter-canister call is only made if the system API ic0.call_perform is called, e.g. by using the CDK's call method. In Motoko, await always commits the current state and triggers a new message send, while await* does not necessarily commit the current state or trigger new message sends. See Motoko await vs. Motoko await*.

Note that if the code does not await the response, the code after the callback is executed in the same message, until the next inter-canister call is triggered using await.

Also, multiple outgoing calls can be triggered in parallel from the same message execution; see the Rust and Motoko examples.

- Property 3: Successfully delivered requests are received in the order in which they were sent. In particular, if a canister A sends

m1andm2to canister B in that order, then, if both are accepted,m1is executed beforem2.

Note that this property only gives a guarantee on when the request messages are executed, but there is no guarantee on the ordering of the responses received.

- Property 4: Multiple messages, e.g., from different calls, can interleave and have no reliable execution ordering.

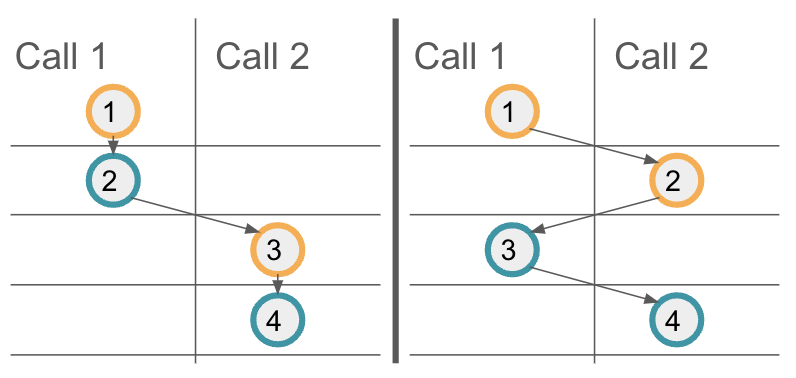

Property 3 provides a guarantee on the execution order of messages on a target canister. However, if multiple calls interleave, one cannot assume additional ordering guarantees for these interleaving calls. To illustrate this, let's consider the above example code again, and assume the method example is called twice in parallel, the resulting calls being Call 1 and Call 2. The following illustration shows two possible message orderings. On the left, the first call's messages are scheduled first, and only then the second call's messages are executed. On the right, you can see another possible message scheduling, where the first messages of each call are executed first. Your code should result in a correct state regardless of the message ordering.

- Property 5: On a trap or panic, modifications to the canister state for the current message are not applied.

For example, if a trap in the second message (blue box) of the above example occurs, canister state changes resulting from that message, even earlier in the blue box, are discarded. However, note that any state changes from earlier messages and in particular the first message (orange box) have been applied, as that message executed successfully.

- Property 6: Inter-canister calls are not guaranteed to make it to the destination canister, and if a call does reach the destination canister, the destination canister can trap or return a reject response while processing the call.

Every inter-canister call is guaranteed to receive a response, either from the canister, or synthetically produced by the protocol. However, a malicious destination canister could choose to delay the response for arbitrarily long if it is willing to put in the required cycles. Also, the response does not have to be successful, but can also be a reject response. The reject may come from the called canister, but it may also be generated by ICP. Such protocol-generated rejects can occur at any time before the call reaches the callee-canister, as well as once the call does reach the callee-canister if the callee-canister traps while processing the call. If the call reaches the callee-canister, the callee-canister can produce a reply or reject response and the protocol guarantees that the callee-canister's generated reply or reject response gets back to the caller-canister. Thus, it's important that the calling canister handles reject responses as well. A reject response means that the message hasn't been successfully processed by the receiver but doesn't guarantee that the receiver's state wasn't changed.

For more details, refer to the Interface Specification section on ordering guarantees and the section on abstract behavior which defines message execution in more detail.